Austin skyline- by me

Transient- weekly photo prompt

Austin skyline- by me

Transient- weekly photo prompt

That means it’s time to dance on a martini glass. Care to join me?

by CD-W

Cono and his grandfather, Ike

Further up on the right is another house. It looks kinda like an old Wayne Dennis house, falling down on one side. Car parts litter the front yard.

“Who lives there?” I say.

“Oh, some damn white man,” says Ike.

“Still like that Cherokee part ’a ye, huh Ike?”

“Damn straight.”

We get to the bar and meet Andres, Ike’s friend. “This here’s my grandson, Cono,” Ike says.

“Pleasure,” I say, shaking his hand.

The three of us sit down at a table for four and a short little old lady in a Pink uniform comes over to take our order.

“Bring us three Pearl beers,” says Ike.

“No beer fer me,” I say.

“Still not a drinker, Cono?”

“Still not,” I say.

“Sody Pop then?”

I turn to the waitress and say, “Ye got Nehi Grape?”

She nods and says, “Be right back.”

For eleven o’clock in the morning the place is busy. The early lunch crowd has come in. Andres starts to talk while Ike listens. And I’ll be damned, Ike’s twirling his index finger around his thumb. They say an apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. This is one habit Dad’s pulled down from his father, but as far as I can see, and unfortunately, the only one.

Ike starts to talk but Andres keeps saying, “What are you saying? I can’t hear.”

Finally, after gulping down his beer, Andres says, “Hell, let’s go someplace quiet where we can talk.” I pull out my wallet to pay but Ike says, “Put that away, Cono. You need ta save yer money.” I do as I’m told, grateful of the man beside me who appreciates my hard work.

Ike and me gulp down our drinks and head down the street to a little dive of a bar, a place that doesn’t sell food.

“This is better,” says Andres. We all sit down at a table and order another round from the bartender, the only person working here.

In the middle of cow talk, a man with a black mustache that matches the color of his eyes opens the door, pulls out a pistol, and shoots a bullet right past Ike’s ears and into the mirror behind the bar. The bartender pulls out his shotgun, aims it at the shooter and says, “Jose, you drop that gun right now. This ain’t no way to settle a bar tab.” The man backs down and yells something I don’t understand, and then he leaves.

As cool as a cucumber, Ike clicks the left side of his cheek, turns to Andres and says, “Ye got another quiet place ye wanna go?”

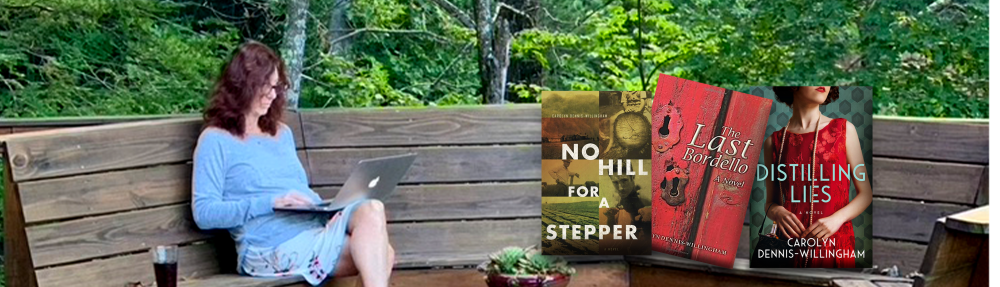

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper

Yesterday, I finally went to Graffiti Park. Castle Hill (the Castle itself once was once a Military Institute) was supposed to be a building development. It failed but the concrete walls remained. So, guess what sneaky graffiti artists did? They painted. And painted. Now, with permission, you can create your own graffiti art. This means that every time you go, you’ll find it different. Cool, huh?

My friend, David Stalker, captured this image last night in his backyard! A male Eastern Screech Owl. Click play to hear him!

Wow! A friend sent me this link about a painter, Felice House, who changed the “sexy cowgirl” image into the powerful.

Click here to see the entire collection and to read the article.

Cono, my father, age 14

You don’t really know much when you’re born, but that’s where it starts, alright, whether you like it or not. When you’re just a little suckling pig on your mamma’s teat, all you really want to know is that the teat will keep filling up so you can start suckling all over again. Once you reckon the food’s always gonna be there, you move on to wondering whether you’re gonna be kept safe from harm and warm when it’s cold. As you get a little older, you find out that maybe there isn’t always going to be enough to eat after all, and you won’t always be warm either. This is especially true if you grew up during the Great Depression in Texas, in the western part, where any stranger is sized up from boot to hat, if, that is, they’re lucky enough to own both.

Texans trust themselves first and foremost, and then maybe one or two of their kinfolk, as long as they’ve found that trust to be right as rain, if the sun can set on their words. I grew up trying to figure out who was in which category, who I could trust and who to never turn my back on. There was a lot of line crossing. I learned what I know from watching those who crossed over and the others who stayed on their own side.

I did both.

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper, my father’s story

I love looking at the past. I took this photo yesterday when I was downtown. These old railroad tracks have existed for over one-hundred years. I wonder if the new buildings will as well.

Almost every time I get to one of those revivals, the grown-ups say, “Cono, don’t you want to be saved?”

“From what?” I say.

“Why the Devil hisself,” they say and then they add a bunch of amens to go along with it.

Unless they’re thinking about Dad being the Devil, I just say, “No thank you.”

“But what are you waitin for? We could baptize you right now and all your sins would be forgiven and you would have eternal life.”

As far as sinning goes, I guess I’ve done my fair share of it, Amen.

“What’s ‘eternal’ mean?” I ask.

“Well, it means you’ll live forever with Jesus right next to you.”

I picture Jesus standing right next to me, while I’m thunk, thunk, thunkin’ on a woodpile forever and ever into eternity, and it doesn’t appeal to me one iota. Last year when we lived with Aunt Nolie, I didn’t have much chopping to do. But now, I have to chop all the time, Chop, chop, chop to make sure Mother has enough wood for the cookstove at the Tourist Court. Chop, chop, chop so Dad won’t lay into me.

Anyway, I’ve heard stories about how some churches take a poor person’s last dime so they can put more gold up by the Jesus statue. Then, a pennyless old woman with only one shoe and five starving children crawls away with her head all covered up, as if she’s ashamed of being broke. It doesn’t make no sense to me whatsoever. It seems to me that Jesus would want you to keep most of your money so you don’t have to starve and die and can at least make it to church to pray. What gets me is watching them churchgoers and knowing that they talk all big about Jesus, but when they get home, they just keep doing their sinning anyway, like they’d forgotten every word they’d learned. Maybe all you have to do is say you believe in Jesus and then you’ll be saved no matter how you act. But what do I know? I ain’t been saved yet.

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper, my father’s story.

Yippee-ki-yah! My mini Aussie is proof. He’s sitting in our sure-fire sign of spring– beside our state flower, the Bluebonnet. (So named by our state legislature in 1901)