Two canvases and acrylic paint.

Two canvases and acrylic paint.

Reblogging about reblogging. 🙂

Before Olvie gets a chance to say anything, I stare at this boys black and white railroad pants and the oversized sports coat that covers part of his white t-shirt. His black hair is cut short, but it’s curly. Not straightened like some Negros I’ve seen downtown around Congress Avenue. He gets closer. His expression sits somewhere between shame and anger.

Tanner’s not a grown-up. Maybe somewhere around my age, but it’s hard to tell since he’s not much taller than me.

Mr. Ford clears his throat. “Mrs. Monroe, this here’s my nephew, Tanner Ford. My sister’s son. Came here from Alabama for a visit.”

“So? Why would I care?” she says, rude like always.

“Miss Monroe,” Tanner says, his eyes downcast. “I threw that rock. I plan to get a job here while I’m visiting. I’ll pay for it.”

The only part of Olvie that moves is her mouth when it drops to her chin.

While we wait for Olvie’s voice to return, I say, “I’m Grace Cooper. I’m staying here until my folks get back from—”

“Overseas,” Olvie says. “And you will address me as Mrs. Monroe. You hear? ”

Tanner looks at his uncle and squints like I did when Mom told me about Olvie. Although she’d never been married, she pretends to everyone that she had.

“And before you ask, I’m not kin to Marilyn Monroe,” she say. “She’s been dead a year now and I’m still here.” Olvie finger-poke-poke-pokes his chest. “And you’re damn right about paying me back. I don’t like having my little house look like a shanty with cardboard windows. Next thing you know, some people will think it’s okay to throw appliances on my front lawn. And, you gave this girl quite a shock. I was afraid I’d have to sit up with Chicken Coop last night so she wouldn’t have nightmares. Such a shock for this poor girl. That’s right.” She turns to me. “Might still have to sit in your room till you go to sleep, right Chicken Coop?”

I shrug at her foolishness. She knows better than anyone how we have our windows broken all the time. A lot of pissed off folks don’t like my parent’s beliefs on Civil Rights.

I look at Tanner. He’s got the brightest green eyes I’ve ever since on a human being.

And all that glass I had to pick out of Gladys’ wig, poor thing.”

When Tanner looks puzzled, Mr. Ford whispers something in his ear. Probably reassuring him that Gladys isn’t human.

Come to think on it,” Olvie continues. “You can start tomorrow. My utility closet needs sorting. You’ll do it for free, of course.”

“Okay,” Tanner says.

Mr. Ford gives Tanner a soft thump to his arm.

“Yes, ma’am,” Tanner says.

“First thing in the morning. And I get up at seven.” Olvie looks up. “Oh, wait just a gosh darn minute. You’re not in some kinda trouble are you?”

From my work in progress set in 1963.

Dad’s been drinking. He sways his way over to me with a look on his sorry-ass face that says, “Ya best answer this next question the way I wanna here it. Where’s Zexie?” He didn’t ask where Pooch was. He could see him lying in the shade by the house.

“What?” I say, trying to keep my axe swinging in the right direction.

“I said where’s Zexie?” he yells.

Unlike Dad, time is standing still and sober like at the picture show, when the film has snapped and nobody knows what to do with themselves. All I know is, I’d been doing what I was told. I was chopping and sharpening, chopping and sharpening all day, the sharpening part being my idea. I have enough wood stacked up to make it through a blizzard.

I say back to him, “I don’t know, haven’t seen her. Been chopping wood all day.”

“Get the gun,” he says. “We’ll follow the trap line. See if she got caught up.” I run inside and get the single shot .22 off the chester drawers and run to catch up with Dad.

Sure enough, Zexie is lying in the first trap we come to, poor little thing. She’s been gnawing on her own leg to get out of that trap. I know I didn’t have anything to do with it. Dad set that goddamn trap, not me. I was only doing what I was told.

Dad pulls the trap open and picks her up, cradling her in one arm like a baby. Then he walks over and slaps the living hell out of me with the other. I stumble back but this time, I don’t fall. I make myself stand up straight.

Dad sure does like dogs.

He hands me the .22 to carry back and starts walking towards the house. Just as I’m thinking, “Don’t turn around you sorry son of a bitch ’cause I’m gonna shoot you in the back of the head,” he turns back around, grabs the .22 right out of my hand, and take the bullets out.

“Here,” he says, and hands the pistol back to me.

He doesn’t trust me, and I don’t trust him. That’s about the sum of it.

I know exactly how it feels to be caught in a trap, and I’ll be damned if I gotta gnaw off my foot to get out of this one. I also know there’s a way to have supper without feeling poisoned. I just have to figure out where that is and which direction I need to go to get there. I’d follow those railroad tracks anywhere about now.

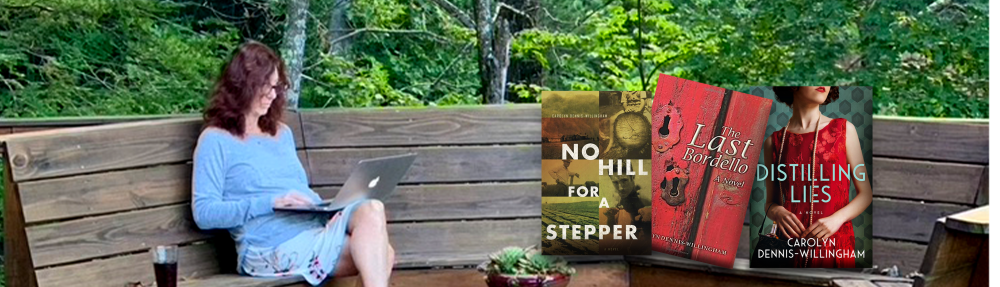

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper

Author note: This is a true story and I need to tell my readers that Zexie recovered.

“Let yourself go. Pull out from the depths those thoughts that you do not understand, and spread them out in the sunlight and know the meaning of them.”

― E.M. Forster, A Room with a View

by CD-W

“You have brains in your head. You have feet in your shoes. You can steer yourself any direction you choose. You’re on your own. And you know what you know. And YOU are the one who’ll decide where to go…”

― Dr. Seuss, Oh, The Places You’ll Go!

my abstract art

Where are YOU going today? 🙂

before I Unraveled him. Literally.

I don’t sew. Really. But man, do I love fabrics. So, I got my mother’s 1970’s Singer fixed. I’m terrified of the thing.

I started the first of my grandchildren’s Easter Bunnies. The ears came out extremely wonky, the face almost distorted. I unraveled the thread and started over. And started over. And, started over, my patience unravelling with the orange thread.

But now, I’m done. I know it’s not perfect but, as I like to say, if it was perfect, nobody would believe I’d created it.

Okay, back to working on my latest manuscript….

Imagine having to protest for your right to be admitted into Officer Candidate School.

When that conflict is resolved, you become a second lieutenant in the Army. But then, on an Army bus, you confront the Army Bus driver for telling you you have to sit in the back. The military police takes you into custody. You complain about the questioning and an officers recommends you be court-martialed.

You are transferred to a different Battalion where the commander charges you with several offenses including public drunkenness. But you don’t even drink. Thankfully, months later, you are acquitted.

You leave the Army and play baseball in the minor leagues. But you are not allowed to stay with your teammates. Still, you prove yourself – big time.

On this day in 1947, you are signed to a major league team- the Dodgers. During one game, the manager of another team yells “go back to the cotton fields.”

And something strange happens. Your teammates stick up for you. Then, in 1962, you are inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Way to go, Jackie Robinson!

Young Cono Dennis

Mr. Pall thinks he’s tougher than a pair of old leather boots, probably because he used to be some kinda wrestler or something. He isn’t nearly as tough as Dad, who last week had beaten a man unconscious on Main Street just because the man spouted off to him. I walk into his office, where’s he’s sitting behind his desk looking puffed up with importance.

“Cono, were you smoking in the schoolyard?”

“No sir, I wadn’t.”

“Were the Allridge boys smoking?”

I think, Why didn’t ye just call them in here like you’ve done me?, but I don’t say that. Maybe it was Mr. Pall’s brother-in-law, who Dad had beaten up last week.

“I have no idee, sir,” I say. “I reckon you ought’a ask them.”

His right eye stares a hole in my left eyeball. His left one kinda wanders around on its own, like it’s been punched one too many times. Maybe he grunts with Mrs. Berry on occasion.

He opens up his desk drawer and pulls out a rubber hose. He thumps it on the desk a few times and says, “Well, I need to whip you with this hose.”

I stare back into his bad eye with both of my good ones and say, “Go ahead, sir. But I jes’t half to tell ye that my daddy said if you ever laid a hand on me, he’d have to come up here and whup you.” I say it real nice though.

He sits real quiet in his principal’s chair, like he’s picturing himself drawing a crowd on Main Street while my dad beats the tar outta his one good eye. While he’s chewing on that idea like a piece of gum, I’m busy staring at him, thinking that his front teeth stick out so far he could eat an apple through a keyhole. After that picture in my mind, I’m not scared one little bit.

Finally, he says, “Git on outta here, Cono.”

“Yes, sir,” I say, ’cause there’s no sense in not being polite.

At lunchtime I’m eating my sandwich, minding my own business, when Tommy scopes me out and says, “Cono, what’cha got fer lunch?”

Even though he’s five times bigger than me I say, “It don’t make no difference ’cause ye ain’t getting none of it.”

“Cono, you shouldn’t a’ stuck that knife in me that time.”

I look up at him with a face as serious as Dad’s and say, “Tommy, if ye mess with me in any way, shape’r form, I’ll cut yer head plumb off with the same pocketknife I used before.”

And just as I’m picturing his dead body without a head like Wort Reynolds, Tommy Burns walks away.

School’s out for the day, and it was another discouraging one. I grab Delma’s hand and start walking back home, now having a little time to think about what happened.

The Allridge boys had been smoking like a bunch a chimney stacks, but I ain’t one to rat on somebody else when it’s none of my business. And, I like to think that Dad would beat the tar outta Mr. Pall if he laid a hand on me. But Dad never said that. If Dad ever finds out that I lied, I might as well curl up in a ball and prepare myself—or maybe just grab my axe.

Lying isn’t always a bad thing. Sometimes, we have to lie in order protect ourselves and the people we care about.

An “eye for an eye” is what I did today. Maybe that part of the Bible makes sense after all.

From No Hill for a Stepper, the story of my father growing up in poverty during the Great Depression.

On this day in 1912, first, second and third class passengers of the RMS Titanic were filled with hope and excitement. It promised to be a grand adventure — not just the travel itself, but the thought of docking in New York City. They had four full days of entertainment and hopefully, fun. Then we all know what happened on the 15th. Of the 2,224 passengers and crew, more than 1500 died. The people in third class had a higher rate of casualties. To see an interesting collection of recovered artifacts, check here.

photo credit