Instead of Uncle “No-Account” Red taking young Cono to buy a donkey, he takes him to a bar in Sweetwater. Cono doesn’t know it yet but he will soon return with his pistol-toting Aunt Nolie. (1930’s)

No-Account gives Sunshine a pinch on her round butt and she lets out a sound somewhere between a squeal and a giggle sound. It sounded stupid.

Sitting there by myself doesn’t stop me from staring, disgusted-like at their carrying ons. She whispers in his ear, he gives her a little smooch, he whispers in her ear, she lets out another harebrained giggle. I get so fed up my belly starts to twist around and I think I might just puke. Standing up I say, “I’m gonna wait in the truck.” And that’s what I do.

I look around the truck, but it’s not there. Not one rope. That sorry son of a bitch never intended to buy me a donkey.

I watch people go in and come out and think about the loser I’m with, the jackass full of bullcorn. My hard-earned-honest-days-work-seed-selling money had gone straight towards something to do with that blonde haired giggly eye winker named “Sunshine.”

No-Account finally gets back in the truck and starts jawing again about more things that don’t make no sense. The difference is, this time he’s swerving around the road like a drunk man, which he is.

He seems to have forgotten about buying me that donkey since we’ve driven past the donkey field for the second time. I look over at him. He’s got a shit eating grin on his face that tells me his mind is sitting on something else. Wink, wink.

That grin flipped over real quick when we got home.

“Where ye been so long and where’s that donkey?” screams Aunt Nolie.

“Couldn’t get one today,” he says.

Aunt Nolie looks at the mad on my face and yells, “What the hell were ye doin’ then?”

No-Account whistles himself into the other room and ignores her.

“Cono, where ya’ll been?” she asks, her tone a little softer now.

“We went to Sweetwater to the Lucky Start beer joint.”

“Why didn’t ye get a donkey?”

“He wouldn’t stop fer one,” I tell her. Then I add more of the honest truth. “Red had some beers and started kissin’ on Sunshine.”

“He was, was he?”

“Yep.”

“Com’on, Cono. I’m gonna get my pistol and I’m gonna drive right back over there and shoot that no-good hussy.”

“Ye know who she is?”

“Everybody in Sweetwater knows that slut.”

I decide right then and there that another ride to Sweetwater to shoot Sunshine didn’t make no never-mind to me. I don’t have a donkey and nothing to strum but and idea.

After Aunt Nolie gets her gun, we’re back in the truck. She puts on some kinda girly scarf and ties it under her chin. Then she takes out her lipstick, looks in the rearview mirror and smears it on her lips. Aunt Nolie must want to look good when she shoots No-Account’s girlfriend.

Here I go again, on the way back to Sweetwater. Not to get a donkey but to shoot Sunshine, My Only Sunshine.

Driving down the highway, Aunt Nolie doesn’t talk much, at least not with her mouth. She clutches that steering wheel like she’s about to squeeze all the Texas sand and grit out of it and that’s a whole conversation in itself.

We finally get to Sweetwater and park in front of the Lucky Star Bar.

“Cono, ye wait right here.”

“OK,” I say, since I’ve already met the woman, who’s about to be shot anyway.

I sit in the car, again. I watch the people come and go, again, except this time, the ones that had been going were coming and the ones that had been coming were now going. I wait for the sound of a gunshot, the sound I’ve become familiar with when I hunt with my dad. I wait alright ‘cause there’s nothing else for me to do.

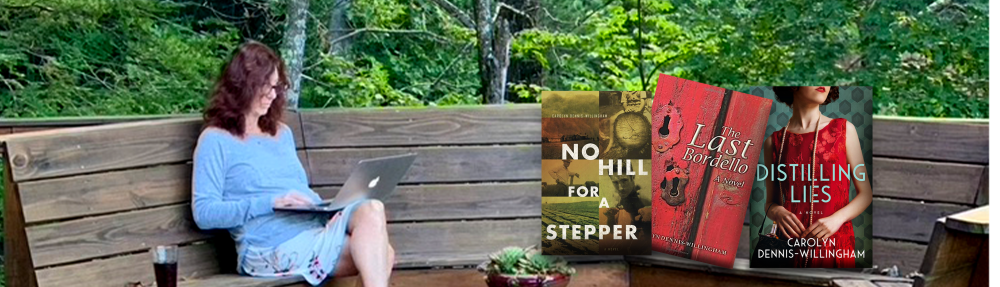

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper