Young Cono Dennis

Mr. Pall thinks he’s tougher than a pair of old leather boots, probably because he used to be some kinda wrestler or something. He isn’t nearly as tough as Dad, who last week had beaten a man unconscious on Main Street just because the man spouted off to him. I walk into his office, where’s he’s sitting behind his desk looking puffed up with importance.

“Cono, were you smoking in the schoolyard?”

“No sir, I wadn’t.”

“Were the Allridge boys smoking?”

I think, Why didn’t ye just call them in here like you’ve done me?, but I don’t say that. Maybe it was Mr. Pall’s brother-in-law, who Dad had beaten up last week.

“I have no idee, sir,” I say. “I reckon you ought’a ask them.”

His right eye stares a hole in my left eyeball. His left one kinda wanders around on its own, like it’s been punched one too many times. Maybe he grunts with Mrs. Berry on occasion.

He opens up his desk drawer and pulls out a rubber hose. He thumps it on the desk a few times and says, “Well, I need to whip you with this hose.”

I stare back into his bad eye with both of my good ones and say, “Go ahead, sir. But I jes’t half to tell ye that my daddy said if you ever laid a hand on me, he’d have to come up here and whup you.” I say it real nice though.

He sits real quiet in his principal’s chair, like he’s picturing himself drawing a crowd on Main Street while my dad beats the tar outta his one good eye. While he’s chewing on that idea like a piece of gum, I’m busy staring at him, thinking that his front teeth stick out so far he could eat an apple through a keyhole. After that picture in my mind, I’m not scared one little bit.

Finally, he says, “Git on outta here, Cono.”

“Yes, sir,” I say, ’cause there’s no sense in not being polite.

At lunchtime I’m eating my sandwich, minding my own business, when Tommy scopes me out and says, “Cono, what’cha got fer lunch?”

Even though he’s five times bigger than me I say, “It don’t make no difference ’cause ye ain’t getting none of it.”

“Cono, you shouldn’t a’ stuck that knife in me that time.”

I look up at him with a face as serious as Dad’s and say, “Tommy, if ye mess with me in any way, shape’r form, I’ll cut yer head plumb off with the same pocketknife I used before.”

And just as I’m picturing his dead body without a head like Wort Reynolds, Tommy Burns walks away.

School’s out for the day, and it was another discouraging one. I grab Delma’s hand and start walking back home, now having a little time to think about what happened.

The Allridge boys had been smoking like a bunch a chimney stacks, but I ain’t one to rat on somebody else when it’s none of my business. And, I like to think that Dad would beat the tar outta Mr. Pall if he laid a hand on me. But Dad never said that. If Dad ever finds out that I lied, I might as well curl up in a ball and prepare myself—or maybe just grab my axe.

Lying isn’t always a bad thing. Sometimes, we have to lie in order protect ourselves and the people we care about.

An “eye for an eye” is what I did today. Maybe that part of the Bible makes sense after all.

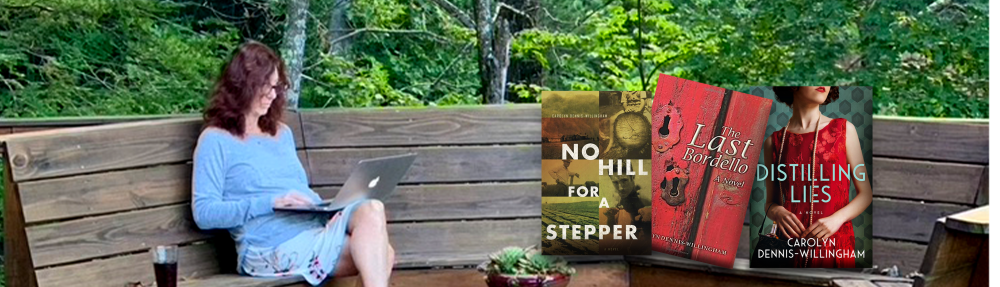

From No Hill for a Stepper, the story of my father growing up in poverty during the Great Depression.

Unravel