Savage. An appropriate name for a butcher.

The door ajar, the stench of raw meat penetrated my nose, but the familiar voice inside stopped me from running past. “Hold on, Sadie.”

“What?” Sadie bent down, retying her bootlaces.

I peeked inside the butcher shop. Miss Reba stared up at the burly man towering over her. “No sir, you must’a misunderstood I’s just—”

“Don’t tell me I misunderstood.” He drew his arm across his chest then slapped Miss Reba across the face with the back of his hand. She tumbled sideways, her head smacking the edge of a table before she hit the floor.

“Colored’s always have to wait,” he added.

My blood curdled as I rushed to her side. “Miss Reba!”

“What have you done?” Sadie yelled behind me.

I knelt beside Miss Reba. “Ach Gott. Are you all right?”

She moaned and lifted a limp hand to the side of her head where blood dripped onto the floor.

“She needs to wait her turn, ain’t that right butcher?” the brute said.

Mr. Savage stood there, his mouth open. The patrons gasped and whispered. No one came forth. What was wrong with these people?

Sadie glared at the man and reached inside her small black purse. She unfolded a man’s shaving knife, stood and approached him. “If I pricked you with this, you’d squeal like a stuck pig.”

My mind blurred. What does it take to kill someone? To sacrifice one’s self for a cause?

The bearded man pointed a finger at Sadie. “Whoa, now girlie …”

“And then, our butcher will take you for a hog,” she said. “After hanging you on a meat hook, he’ll slit you from neck to belly until you bleed out. Isn’t that right, Mr. Savage?”

Mr. Savage blinked a few times and cleared his throat. “Sadie, you best look after Miss Reba there.”

The abuser’s nostrils flared. He pointed a finger inches from Sadie’s face. “You need to shut that vulgar trap ‘a yours, Missy. Surely you got a sheriff in town who can lock you up for pulling a weapon on me.”

“ Unmensch! Her weapon?” My words hurled forth, surprising me. “Your hand was a weapon! You hurt Miss Reba.”

Sadie glanced side to side. “We have the best county sheriff in the state. Looks like he’s not here right now. So, the next time any of us return to purchase pork, including this fine lady on the floor bleeding the same color red as everyone else, you might be the pig we get to eat.”

The man clenched both hands into fists. “Why you …”

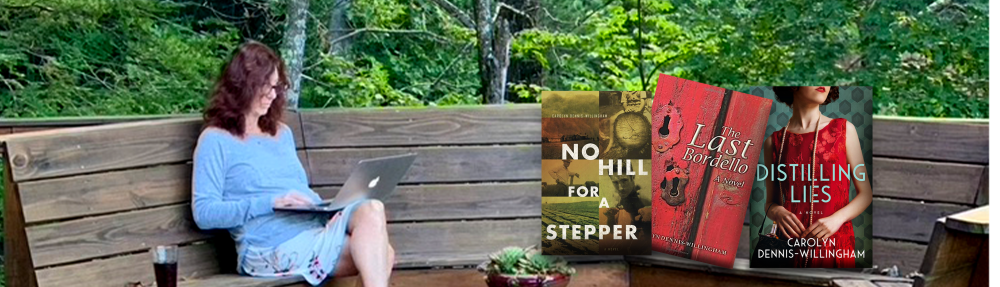

Excerpt from The Last Bordello