Tag Archives: novels

Body Removal

Betty doesn’t look like Betty unless you stare long enough and Miss Helen’s too busy with body removal to take a good look.

“What’s she got, Miss Helen?” Frank asks.

“I have an inkling and, if I’m right, she needs medicine right away.”

They carry her to Moonbeam like soldiers hauling the injured.

“Open both back doors,” Miss Helen snaps at me.

I open the near door first then scramble around to the other side.

“Now come back over here and hold her the front corners long enough for me to go on the other side and pull her in.”

“I …”

“You’re strong enough to hold her up for three seconds, aren’t you?” she squawks.

I take Miss Helen’s place. Now, it’s me who’s keeping up the top half of Betty, but she’s sinking in the middle. Frank stays quiet holding the corners next to his ma’s feet.

Miss Helen climbs in the back seat and grabs the sheet corners by Betty’s head. She pulls Frank’s ma inside Moonbeam like threading a human Yarn through the eye of the needle.

Excerpt from The Moonshine Thicket set in 1928

Driving home from the hospital

We’ve only been waiting a few minutes when Tanner pulls the green and white Pontiac up to the front of the hospital. He hops out of the car, his teeth glistening in the dim light of dusk. Soon, I’ll be the one who makes his smile go away.

He opens the passenger door for Olvie. “Miss,” he says, ushering her inside like a real chauffer.

“How many dents and scratches did you put on Pontiac?” she says.

“Only one.” He smiles. “Buffed out easy as pie.”

Olvie lets out a hoomph. “Think you’re funny, don’t you Wise Guy?”

“Yes’m. Sometimes, my funny bone pops out an’ jes’ makes the white folk laugh.”

“Stop talking like Elias. Your uncle thinks he’s living on some plantation in Mississippi picking cotton for his Master.”

Tanner starts the car and pulls away from the hospital. “Uncle Elias’ Roots are still in his ancestors cotton field. And it’s Massa, not Master.”

I catch Tanner smiling at me through the rear view mirror.

“Don’t you dare stink up my car with slave dialect,” Olvie snarls.

“As long as you don’t dress me up in a moo-moo or as an Injun.”

“Don’t be crude, Wise Guy. I’ll have you know that Fritz is no ordinary Indian.”

“That’s for sure,” Tanner mutters.

Olvie huffs. “He’s an Indian Chief, and don’t you forget it.”

“How do you know Fritz likes being a Chief?,” he continues. “Maybe he just wants to be a mannequin.”

“Why you!” Olvie squeaks.

“Okay, maybe he liked being a Churman and wearing those lederhosen.”

“Shows what you know. The German Fritz got tired of thinking about the damn Nazis’.”

If I hadn’t watched the news, hearing their banter would have put me in a state of euphoria. Tanner seems totally happy, almost like a new person. But, knowing what I know, nothing in the world is funny.

Excerpt from my Work in Process, Olvie and Chicken Coop (working title), set in 1963 during segregation.

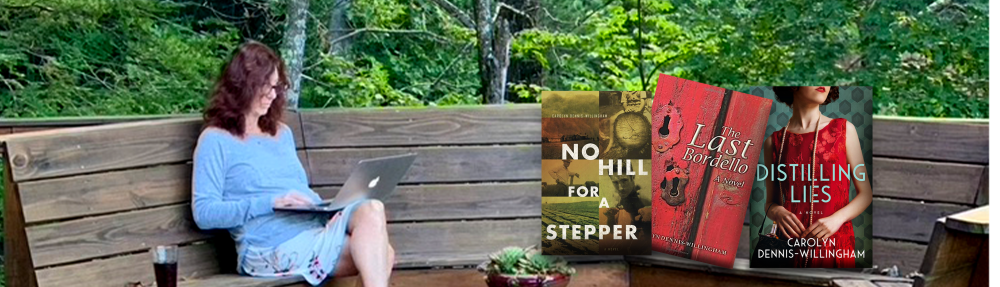

Pictures that don’t match up

I look in my duffle bag and see the sparring gloves Colonel Posey lent to me yesterday He had looked tired to me, like a man defeated from grief but who was still trying to stand up straight. His hair was Graying, and his eyes had lines at the corners like a map of a busy town. But his kindness sat on my chest like Pa’s and Ike’s kindness, stayed there perched like a redbird.

I thought about when Colonel Posey’s little daughter had died six months back from some disease the doctors didn’t know how to cure. I thought about Ervin Clay Carter and Gene Davis, them being dead and how hard it was on their parents and, maybe, how hard it was on me. They were just kids and life had sucked the air out of them easier than sucking a chocolate malt through a thin straw. Then I thought about Private Henderson.

After I’d told Colonel Posey about sparring with my father he said, “You know, whatever picture you’ve formed in your head about sparring with your father might not be what really happens.”

I knew what he was talking about. I thought of other pictures I’d made up in my head that didn’t match the truth, like working on that pipeline. That picture wasn’t anything like what happened. I thought of more pictures from long ago, like me owning my own guitar, or having a real conversation with my dad, or being able to reach my .22.

Drunk and crazy cowboys

Ike, my great grandfather, at age 23

Ike, “Is’ral”, in later years

According to Grady, Logchain and “Is’ral” got real liquored up, the two of them drunker than Cooter Brown. They hopped on top of Nellie, Ike’s old Gray mare, and rode straight into the lobby of the Gholson Hotel. As if that wasn’t bad enough, Nellie wore a bell around her neck that swayed back and forth like it was ringing an announcement that the two Cooter Browns were itching for havoc. Fire Chief Murphy chased after them, hollering for them to stop their nonsense. Instead of stopping, they roped ol’ Fire Chief Murphy and pulled him around a little bit. They didn’t hurt him none, but the madder the chief got, the more they laughed their fool heads off.

When Fire Chief Murphy finally freed himself from the rope, he just brushed off and mumbled, “Damn fools.” Then he walked off shaking his head like he still had dirt in his ears from really being dragged in the road.

That wasn’t the end of it. Ike told Pa he needed to go to the barbershop for a shave.

Pa says, “Aye, God, Is’ral, ain’t no need te pay Grady for a shave. I’ll do’er fer free.”

“Well,” says Ike, pondering the idea and probably clicking his cheek. “Alrighty then.”

They stumbled into the barbershop, and Ike walked over to Grady’s barber chair where he plopped down his dusty butt. Pa threw the shaving towel over him and lathered him up real good with the shaving brush. Grady said he just stepped aside and leaned up against the wall with his arms folded. He told me it was better than watching a picture show.

After the first nick, Pa slapped a little piece of paper over the cut and kept on shaving. After the second cut and the second little piece of paper Ike says, “Don’t ye be drainin’ m—” but Pa slapped a piece of paper over his mouth, so he’d shut the hell up saying, “Quit yer bellyachin’, Is’ral.”

By the time they walked out of the barbershop, Ike’s face was covered with those tiny pieces of paper. From cheek to cheek and nose to chin he looked like he’d walked out of a mummy’s tomb.

Grady said he was laughing so hard he barely heard it when Ike mumbled, “Logchain, it’s a miracle you didn’t cut my head plumb off.”

Then, those two crazy cowboys got back on that old grey mare, her bell just a ringing and rode off to who knows where to do who knows what else.

From No Hill for a Stepper, my father’s story.

Meta pretends she’s a prostitute

His lips mashed together into a thin line. “Hey, wait just a confounded minute. Did you say…? They didn’t hire you to, you know…”

Retaliation. “Yes! I got a job there, and I know I will love it. The clients can be quite challenging. Last night, when I had to explain that I wasn’t warmed up yet—”

“I don’t want to hear more. Hell, I might be street-smart, but I haven’t even turned fifteen yet. Porca miseria!”

“Porca what?”

“Just practicing on not saying ‘shit’ all the time. Ma doesn’t like it, and my little sister thumps me between the eyes when I say it. It’s a little Italian cuss word that means pig misery. Like saying ‘damn.’ Where you off to, anyhow?”

“My Aunt Amelia’s. Would you care to accompany me, Mr. Scallywag? I found a job because of you, did I not?”

He tore the cap off his head and rubbed his greasy black curls of hair. “Stop saying that. I had nothing to do with you getting that job!” He pointed his finger eastward and accelerated his pace.

“Oh, but you did,” I said, hurrying to catch up. “If it hadn’t been for you, I wouldn’t be tingling with avidity for this evening to arrive. That’s why I’m going to visit Aunt Amelia, to tell her the good news.”

“What’s avidity mean? Wait, you’re going to tell your great-aunt about your new job? At Fannie Porter’s?”

“Of course. She’ll be thrilled for me. Besides, she knows I’m good at it. I’ve been doing it for years now.” I muzzled the smile aching to form.

His eyes widened into a dumbfounded glare.

“And avidity means eager, like being Avid about something.”

“I gotta go,” he said, turning away.

One more chance at deception. “Giovanni? You said you were fourteen?”

“Yeah. Why?”

“Well, you are too young to be entertained at Miss Fannie’s. However, I’ll ask her if you can watch me perform sometime.”

His jaw dropped, his dander standing taller than his five-foot-five stature. “You want me to…watch?”

“Ah, we’re here. Thanks for the company.” I trotted off with the last laugh.

From The Last Bordello, historical fiction set in 1901

Emma June remembers something

“Shut up, Betty. You’re drunk.”

“Not enough. I thought this would be easier. I would never have told you except, except, well, now we need your help. The money’s dried up. You’re my only friend.”

“Friend? You’re not my friend. You’re a liar, a traitor. How could you?!’

Mama’s crying now and I think I have to upchuck again.

“But Bernie, I’m all he’s got. And if I don’t have help, I’ll be forced to, to tell everyone. Everyone!”

My head hits the back of Beauty’s seat. Mama has screeched the Model T to a halt.

“You’re threatening me now?” Mama’s words are Spikey like cactus needles. She never yells like this. “Is this why you befriended me in the first place?” Mama sobs. “For money? For …”

It still doesn’t make sense. The only thing that does is being home with Daddy.

I stumble through my front door trying to breathe.

“Emma?” Daddy says. He rushes to me with arms wide enough to hug all of Holly Gap. Choppers licks muck from my face.

“Oh, Daddy, Daddy.” I let him hold me.

He lifts my chin and stares at my dirty, scratched face. “What happened, Emma June? Tell me.”

His voice is worried. But there’s no truth I can tell him. Not now.

Excerpt from The Moonshine Thicket, 1928

Let Worm-God help with your writer’s block

Note: Don’t tell her you don’t believe. She hates it when creativity is stifled.

She started out as a mere, mealy book worm.

She has read ALL of your work and she waits for more. She lives in her heaven beneath the earth surrounded by tunnels and tunnels of shelves filled with writings from authors, books of all genres from every year. When the others around her noticed this magnitude, they had declared her Worm-God.

At night, she listens. She hears the crumpling of paper, the slam of a laptop, the author’s piercing whine.

She ascends. She is careful. She waits until you nod off, then wiggles imperceptibly between your fingers and leaves a residue of inspiration. When she is finished, she returns below.

The next morning, you rise, pour a cup of coffee or tea, check emails. You pop your knuckles and begin.

Deep below, Worm-God makes room for your new book. As she waits, she smiles.

By the way, she will also nudge you into sending off your manuscript.

animated image credit

Haters

I can’t see anything out of the ordinary, only Olvie’s backyard. But I hear it. Words my mother has heard slammed in her direction.

“<N…> lover!” the boys chant.

Five of them emerge from the backyard bushes and run towards the front yard.

I grab a frying pan and head for the front door.

“Cooking out tonight?” Olvie says.

I ignore her and run outside.

Boys scramble in the cab and the back of the pick-up truck and shoot me the bird. Kent, the last one in, glares at me. “Beam that Fry pan over your own head, Grace. You’re not thinking straight.”

They peel off. Hearing the frying pan slam the sidewalk gives me a bit of satisfaction. But not enough.

“Chicken Coop?”

Olvie stands on the porch, her eyes pinched and curious. “Somebody got shot?”

The damp cloth feels good on my forehead, but I could forego Gladys’ positioned arm against mine.

“Want me to call that imbecile Garvey?” Olvie says sitting next to me on the leopard skin couch.

I shake my head. “He couldn’t do anything anyway. Name-calling’s not against the law.”

“So, who were those ragamuffins?”

“I only know one of them. They called me a <n….> lover.”

“Next time,” she says, “Don’t be so stupid. Pull out the cast iron skillet instead of that cheap enamel one. No, never mind that. You’re too scrawny to lift it. Be best if you grab the baseball bat under my bed. But if you swing it, don’t miss.

“I don’t want to be violent,” I say, trying to sound like my parents.

“You hear what I said? Don’t miss.”

Shining Bosoms

Mama liked Miss Helen’s moonshine, but only when she drank with Beauty. Once, when the summer was too hot for anything else, Mama, Scooter and me, took Beauty to the swimming hole. Mama spread out a red blanket and plopped a picnic basket on top. Scoot and me ate cheese and tomato sandwiches and crunched apples while Mama and Beauty drank Miss Helen’s hooch out of paper cups. Beauty got so ossified, she stripped naked and jumped in the creek. It Jolted me a bit, but Scooter didn’t care on iota.

“Betty Bedford, get out of the creek before you drown,” Mama said, laughing.

Then Beauty stood up in water only waist deep, her bosoms shining with moisture. She’d laughed and said, “Hard to do unless something pulls me under.”

No matter where we went, Mama and Beauty always had fun together. Except when everything went wrong.

Excerpt from The Moonshine Thicket