I wrote this shortly after my father died in 2009. (Happy Birthday, Daddy)

Dear Dad,

I write. My eyes blur. I see a cowboy hat with a cowboy underneath it. You’d say, “This hat’s worth a lot more than what’s underneath it” . We knew better each time you said it. You are worth more to me than you’ll ever know.

When I was in the Brownies, we went to a father/daughter banquet at the middle school and your job was to identify my feet under the stage curtain. I sat behind that curtain for only a short time when I heard you say, “is that you Carolyn?”. “That’s me Daddy” I said. You found my feet before I knew where they were going to take me.

In Girl Scouts, you told me I had made a fabulous speech in front of a large audience when in fact, I had stood there, a frightened girl in uniform, with all my words stuck in my throat. I was silent and scared, staring into the crowd of strangers. You were the only one who heard my silent words, like they were loud and clear and perfect. You said I did just fine. You made me not hate myself that night.

You threw that football with me in the front yard and always encouraged me. You taught me how to drive. You said to never forget where my break was.

You taught me how to love my dogs, how they held our hearts and souls within them, in case we forgot where and who we were. Thru them and other things, you taught me that your heart was sensitive and kind.

You told me bedtime stories, like the three little bears. “AND THERE SHE IS”, you’d say and I’d laugh like it was the first time I’d ever heard it.

And you were the one who taught me how to pray.

Just a couple of weeks ago, I was at your house putting on my hands wraps for my boxing class. You wanted to know how fast I was so you speed-drilled me by putting your hand up. Your past boxing memories were still alive. You were always in my corner, pulling for me, taking care of me when I was hurt. My Dad, my cornerman.

On Father’s Day while you laid in bed, I brought you the painting I had done of a cowboy silhouette. You looked at it and said, “that’s me riding off on my last sunset.” We all knew you were ready for that ride.

I believed you when you told me you would always look after Pat and I after you had gone. You said, “I always take care of my babies”. And now I hear you say, like you’ve said a thousand times before, “if I tell you a rooster wears a pistol, look under it’s wing.”

You didn’t plan the first part of your life but you lived it, felt it, analyzed it and learned where you were going next. You wanted a life with stability, you met my mother and you lived the next 6o years on a level ground. And then? When it was time for you to die? Somehow you figured out how to put all your ducks in a row and be buried on your anniversary. So Dad, when I get sad I will know where you are, together again with my mother, exactly where you are supposed to be.

And as your grandpa, Ike, always said with his sarcastic grin, “ well, aren’t you smart.”

Dad on right with his grandfather

And <to my son and daughter>: Grandpa would want me to remind you of a few things.

1. trust yourself and learn first to be your own best friend.

2. whatever you choose to do in life, make sure you love it.

3. take care of your money

4. <Son>, it’s not time to go, it’s time to dance.

5. <Daughter>, stay away from hairy legged boys.

And as I was laying in the front room of your house, the night before you died, I realized that the times you hugged me from the outside to the in had ended. From this point on, your hugs will be from the inside to the out. And I will feel them always.

You put the “spirit” into my soul, Dad. You were my greatest teacher.

And as you always said, “the cream in the pitcher always rises to the top.”

And there, you are.

With a love that never ends,

Carolyn.

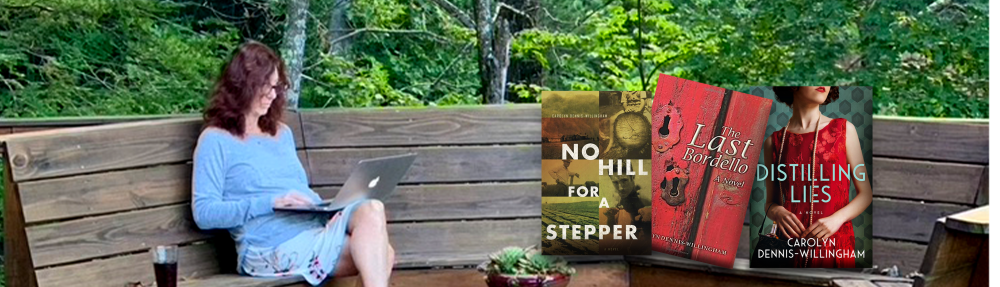

(No Hill for a Stepper is my father’s story about growing up in the Great Depression with an abusive father. My dad broke that chain of abuse)