Dad’s been drinking. He sways his way over to me with a look on his sorry-ass face that says, “Ya best answer this next question the way I wanna here it. Where’s Zexie?” He didn’t ask where Pooch was. He could see him lying in the shade by the house.

“What?” I say, trying to keep my axe swinging in the right direction.

“I said where’s Zexie?” he yells.

Unlike Dad, time is standing still and sober like at the picture show, when the film has snapped and nobody knows what to do with themselves. All I know is, I’d been doing what I was told. I was chopping and sharpening, chopping and sharpening all day, the sharpening part being my idea. I have enough wood stacked up to make it through a blizzard.

I say back to him, “I don’t know, haven’t seen her. Been chopping wood all day.”

“Get the gun,” he says. “We’ll follow the trap line. See if she got caught up.” I run inside and get the single shot .22 off the chester drawers and run to catch up with Dad.

Sure enough, Zexie is lying in the first trap we come to, poor little thing. She’s been gnawing on her own leg to get out of that trap. I know I didn’t have anything to do with it. Dad set that goddamn trap, not me. I was only doing what I was told.

Dad pulls the trap open and picks her up, cradling her in one arm like a baby. Then he walks over and slaps the living hell out of me with the other. I stumble back but this time, I don’t fall. I make myself stand up straight.

Dad sure does like dogs.

He hands me the .22 to carry back and starts walking towards the house. Just as I’m thinking, “Don’t turn around you sorry son of a bitch ’cause I’m gonna shoot you in the back of the head,” he turns back around, grabs the .22 right out of my hand, and take the bullets out.

“Here,” he says, and hands the pistol back to me.

He doesn’t trust me, and I don’t trust him. That’s about the sum of it.

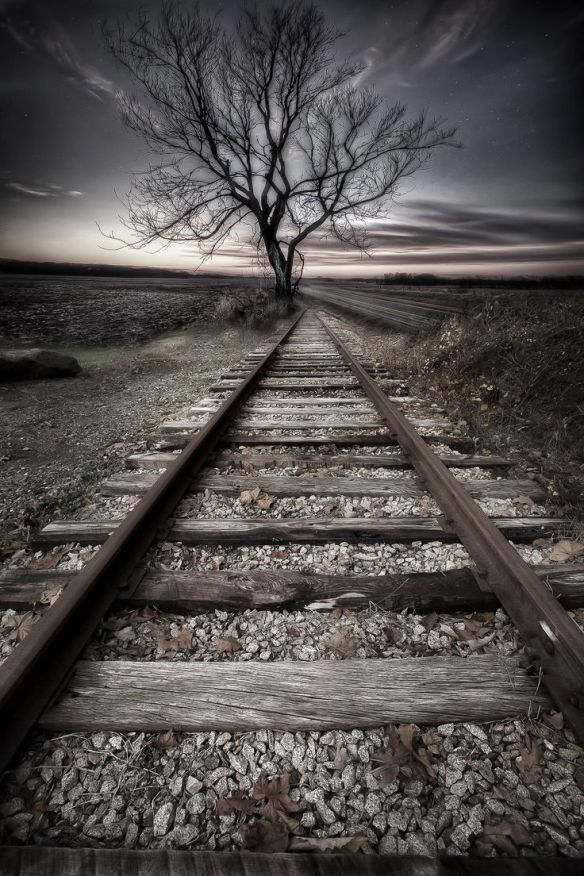

I know exactly how it feels to be caught in a trap, and I’ll be damned if I gotta gnaw off my foot to get out of this one. I also know there’s a way to have supper without feeling poisoned. I just have to figure out where that is and which direction I need to go to get there. I’d follow those railroad tracks anywhere about now.

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper

Author note: This is a true story and I need to tell my readers that Zexie recovered.