Dad can catch a housefly in one hand without blinking, so it shouldn’t have surprised me none that his open palm slams fast across my face.

As I put my hand to my face he says, “Oh fer cryin’ out loud, Cono! I’ll swannin’, ye bit the your new toothbrush in two! Can’t ye do…”

I don’t hear the rest of what he’s saying. He’s walking away from me shaking his head back and forth. Half of my face stinging like it’s been resting on a yeller-jacket’s nest. The other half just feels sorry. How can you build up something so high, just to watch it fall down so hard? With the brush part still inside my mouth and its handle still in my hand, I think maybe I’m not so big after all. I guess I’ve found the baby Devil’s Claw after all. It’s me. I’m the baby.

I think about what I’m supposed to do with these two pieces. Maybe I can just swaller the brush part that’s not doing anything, but napping on my tongue. At least then, half of my dumbness will be covered up. Then again, Ma is always saying to me, “Cono, ye need to ‘member that anythin’ ye swaller is gonna have te come out the other end.” She reminds me about this all the time, ever since she saw me swaller a penny. No sir, she won’t let me forget about that penny. I’d picked it up off Ma’s night table, looked at it, sniffed it and after licking that penny, it just slid down my throat as easy as ice cream.

When Ma saw that penny go in my mouth and not come back out the same way, she said, “Times bein’ hard, ye gotta look at yer ba’ll movement ev’ry time ye do one. Don’t use the outhouse. Go in the fields. When ye find it, clean it off real good and hand it over to yer Mother. She needs it a whole lot more’n yer belly does.” I knew she was right. No one has much money. Most folks around here are six pennies shy of a nickel.

I watched each poop that turned up. I waited hoping it had melted and I’d already peed it out, but that didn’t happen. A few days later, when I saw that penny come out, I stared at it for a while. I just didn’t have it in me to pick it out of my poop and clean it off.

Every few days Ma would ask, “Find that penny yet, Cono?”

“No ma’m,” I’d say, “Must be makin’ its way back up.”

Now if I would have swallered that penny in front of Ike, he would have grinned and tilted his head to the side and said, “Well, aren’t you smart!” Then we both would have laughed and that would have been the end of it. Except, that ain’t the way it happened. It was Ma who saw me swaller that penny.

A few days later, Pa took me to Adam’s Grocers to get us some cheese and crackers like we always do on a Saturday. We sat on the breezy side of the house and watched the nighttime roll over to our part of town. It was so quiet, that when we opened our cheese and crackers, our crunching sounded like a two-man band. And when the music of summer bugs joined in? We were better than a revival choir.

“See this tooth right here?” Pa says jabbing his finger on a back tooth.

“Yeah?”

He puts that finger up to his nose, sniffs it and says, “It shor’ do stink!” Pa sure is funny sometimes.

Spitting out a cracker crumb with his tongue and a puff of air, Pa reached into his pocket, pulled something out and said, “Here ye go, Cono. I think this is yer’n.” I looked down and smiled at his open palm. There, sitting smack dab in the middle of his calloused farm hand was a shiny penny.

“Thanks Pa,” I said, staring at its purpose.

“Mm, hmm,” said Pa. “Ever’thin’s copacetic, ain’t it Cono?”

“It sure is Pa,” I said. Pa loves that word, “copacetic.” He told me “copacetic” means that things are tasting good on your tongue and that everything’s going to be alright.

I put the penny in my pocket to keep it safe while I ate my crackers. When we’d finished eating and as the sun was getting further and further away from the day, I ran into the house and saying real loud to my mother so Ma could hear, “Mother, I think this is yer’n.”

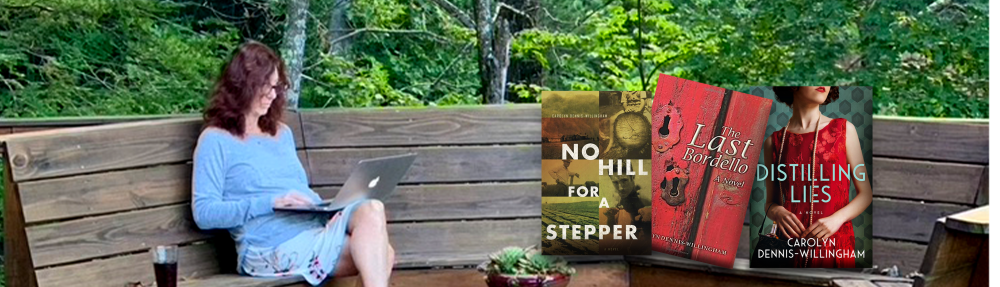

From my novel, No Hill for a Stepper, my father’s story. (available on Amazon)

Lifestyle