One Thanksgiving when we lived in the Tourist Court, we had enough food for Mother to make a real meal, but it was Pooch who landed on Plymouth Rock. We didn’t have money to buy a turkey, but somehow Mother got hold of an old hen to cook. She baked it for most of the morning, even making cornbread dressing to go with it, which, for her, was like pulling a cart full of lead. She set the food on the kitchen table to let it cool while we went to the drug store to get Dad his medicine. Seeing as how it was Thanksgiving, the drug store was closed and Dad had to rely on his refrigerated liquid medicine to make it through the day.

When we got back home, Dad opened the door and what we saw made my mother want to spit cactus needles. There on our kitchen table laid scattered bones where our chicken used to be and only half of what used to be a whole pan of dressing.

We looked around the corner into the bedroom. Lying on Mother and Dad’s bed, head on a pillow and wearing a smile that stretched from Rotan to Sweetwater, was Pooch. We were the three bears coming home to find out that our porridge had been eaten, but this time, not by a little blonde-haired girl but a Curbstone Setter with an eyepatch.

Pooch’s smile disappeared when he caught sight of Mother spitting fire from her eyeballs, and coming at him with a big broom in her hand. Once those straw bristles touched his butt, he was out the door lickety split.

We ate the leftover dressing and the pinto beans, which had been safe from the theiveing on top of the stove. Mother’s teeth were so clenched with madness, I’m still not sure how she got anything into her mouth. Dad, on the other hand, was trying not to laugh, and he looked like he was enjoying every bite of the scant Portions.

“Ain’t it surprisin’ how full we can get without eatin’ meat?” Dad says stuffing more beans into his mouth, his eyes pushed into a squint by his smiling cheeks.

“It ain’t funny, Wayne,” Mother says.

We all stayed quiet for a bit so Dad could concentrate on keeping his food in and his laugh from coming out. Then he mumbled out loud, “Guess we’re not saving any leftovers for Pooch.”

I couldn’t help it. I had to stick my head under the table and hold my breath to try to keep my own laugh from spewing across the table.

Dad leaned back in his chair, pushed his plate away, patted his belly, and said, “I ate so much I think I got a little pooch.” That’s all it took. My sides started to split right along with Dad’s. Delma giggled, and Mother, although she tried to hide it, was starting a grin all her own.

Pooch didn’t show up until later that night, when everything was calm again and the chicken and dressing had settled nicely in his belly.

Even though we had beans, cornbread, and dressing for Thanksgiving, it was Pooch who really celebrated the feast of the pilgrims. And, I think because of that, Pooch had given us a rare gift around the supper table: laughter.

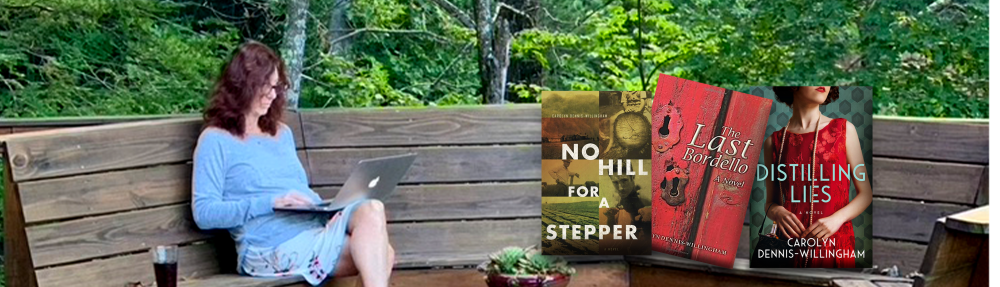

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper (for those who have enjoyed these excerpts, remember you can order the novel on Amazon.

Daily word prompt:Portion