Serene Your Morning AND HAVE A LISTEN

Image

I have a character, and, like most, she just sort of showed up. But now she lies dormant and I ache for her to return. I think about her but can’t rouse the crazy old bat – even now when there’s plenty of time to spend on the computer.

I know Olvie lives alone. It’s the 1960’s and she takes up space in a small house just outside the old freedom town of Clarksville in Austin, Texas. She tries to fix her hair Marilyn Monroe-style but it comes out looking like Sally’s on the Dick Van Dyke show.

Olvie hates calling telephone numbers that contain a zero. Takes too damn long for the rotary dial to circle all the way back to its starting position. And the rabbit ears on her Magnavox don’t work to satisfaction until 10:00 a.m. when Let’s Make a Deal airs.

Until she chunked old Singer out the window, Olvie used to be a card carrying member of the Sewing Guild. She does, however, still have a license to check out books should she have the hankering to stare at words instead of the boob tube.

A real visitor might enter her house and think they have stepped into the Twilight Zone. Mannequin Gladys, wearing her flapper dress, stares out the window. Half-torsoed Fritz wears the top portion of a lederhosen and precariously balances on the television.

When she encounters the poor soul walking past her house, she poke, poke, pokes his chest, asks if she can spit on his shoes, then adds, “it won’t take long.”

Returning inside, she kicks off her duck slippers and does a quick “shuffle off to Buffalo” to impress Gladys and Fritz. They are catatonically dazzled by her performance.

Dear Olvie, please come back so I can plunk your words and actions down on a keyboard. Get in my face, spit on my shoes if you want. Just show up again.

Your friend, Carolyn

image credit

Gene is teaching me how to play checkers. He lets me be red and I learn about jumping and kinging. I think about Grady’s checkerboard and think that next time I might just ask him for a game. We could sit outside at his checker table and watch the rich people go in and come out the Ghoston Hotel.

“Cono, there’s a new kid in town. He’s got two pairs’a boxing gloves.”

“Who is he?”

“We call him Oklahoma ‘cause that’s where he’s moved from.”

“Can I box with him?”

“He’s a little bigger’n you are.”

“Don’t matter. Everybody’s bigger than me, ‘cept you.” Being small doesn’t seem to bother Gene one iota. He knows how to stand real tall in his shoes.

Gene gets us together at the open lot. Of course, I put on Oklahoma’s old pair, the ones with the black cracked leather and torn laces. It doesn’t matter. They feel good on my hands, strong and powerful, like I could reach down and pick up the whole town.

“Ready to box?” he asks.

“Ready,” I say. I try to remember the punches Aunt Nolie has taught me, the ones my Dad used to clobber the Tombstone.

Oklahoma and me start out in the center of the lot, without any ring this time, but with boxing gloves on our third grade hands. He comes at me full force. I swing my arms like windmills trying to get a hold of something. He circles around me, trying to get my attention. He’s already done it. He’d gotten my attention alright, right on my mouth. A piece of my tooth is missing. The fight lasts a whole minute. He beat the tar outta me.

“Ya okay, Cono?” asks Oklahoma.

“Sure,” I say even though I got dog tired after one minute. “Jes’t lost a piece’a my tooth’s all,” I bend down to try to find it.

Gene looks in my mouth to see my broken tooth and says, “Cono, ye ain’t gonna find that tiny piece of tooth, not in this dirt’n weeds. Why’re’ ye lookin’ fer it anyhow?”

“Ya gonna try to glue it back on or somethin’?” laughs Oklahoma. I just shrug my shoulders and stop looking. I don’t want to tell them that I wanted to save it for my box of specials.

When Oklahoma has his back turned, I tear off a piece of the worn lace from my borrowed glove and stick it in my pocket. That’ll have to do.

I’m not a good boxer yet, that’s for sure. But at least now I can say that I’ve worn real boxing gloves, felt the goodness in them and have a broken tooth to prove it. Getting a beating in checkers in one thing, but getting a real beating is different.

I get home and show Mother my tooth.

“Don’t worry none ‘bout it, Cono. When ye grow, yer tooth’ll grow right along with ye and that little chip won’t even show.”

That’s what I’m afraid of.

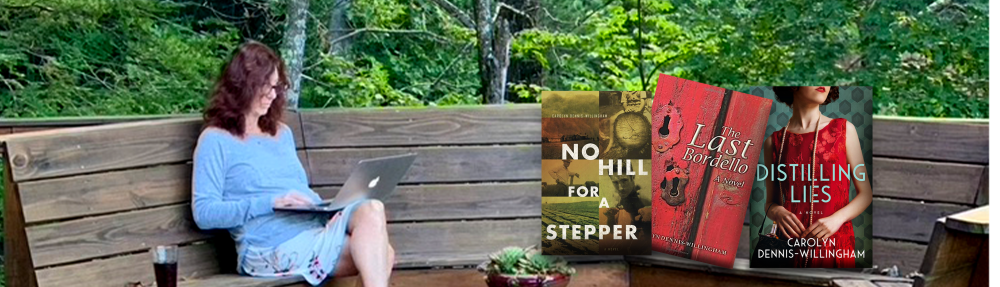

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper, by C. Dennis-Willingham

The “real” Cono (in the two pictures below) grew up to be a boxer in the Army. And later, he became the man I would lovingly call, “Daddy.”

by C. Dennis-Willingham

via Broken

Maybe it was a low point for Dad but for me, it was anything but.

We were living at the Dennis ranch, when Dad came home drunk and decided it was time to act like a real rodeo star. I was standing outside the corral, where we kept one of our two-year-old bulls. Dad saunters over to me and slurs, “ Cono, grab that bull o’r yonder. Hold’em still ‘til I get on. I’m gonna ride this son of a bitch”

“Sure I will, Dad.”

It was better than watching a picture show. While I was putting the rope around the bull’s neck Dad went over and fixed Ike’s spurs to his shoes! Not to his boots because he didn’t even own a pair of boots, but to his shoes! Then he slapped on Ike’s chaps. I helped him get on top of the bull and stood there holding his rope.

“Whenever you’re ready,” I said.

“I’z ready,” he slurred.

I let go.

Dad put one hand up in the air and said, “High, ho, silv……”

That bull didn’t even buck. He just turned around real slow, like he was trying to see what kind of idiot wanted to sit on his back. That slow turn-around was all it took. My Dad fell right off that lazy bull and straight into the dirt, Ike’s spurs dangling from Dad’s shoes.

I turned around and looked in the other direction, so Dad wouldn’t see the laugh in my face. If he was paying attention, he would have seen my shoulders quivering with the same laughter.

He got up and staggered back to the house, mumbling something about killing steak for dinner. Some things sure were funny back then, but other times? You couldn’t find “funny” anywhere you looked.

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper by C. Dennis-Willingham

image credit

via Laughter

Ike Dennis

Ike, my grandfather, ain’t mean like his son. Unless he’s breaking a horse or doing something else with purpose, he’s got a smile perched on his leathered face.

He stays cool as a cucumber even when times are hard. I hardly ever see that worry bubble dancing over his head like a cloud of Texas dust that most of us stand under.

He got rid of his worry a long time ago at the age of two when Great Grandpa Jim put him on top of a horse. If T-R-O-U-B-L-E comes knocking on his door, he just wrestles it off until all that’s left is the T.

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper by C. Dennis-Willingham

via Bubble

I like looking at my teach, Mrs. Alexander, at her nice smile and her fancy dress. I keep picturing my mother getting to wear a dress like that someday.

Right before it’s time to go home, Mrs. Alexander starts to teach us a new song called “Home on the Range”.

“Oh give me a home, where the antelope roam and the deer and the antelope play. Where seldom is heard, a discouraging word and the skies are not cloudy all day. How often at night, where the heavens are bright with the light of the glittering stars, have I stood there amazed and asked as I gazed if their glory exceeds that of ours. Home, home on the range….”

I like those words. They make me feel almost as good as when I’m riding on ol’ Polo, free and easy like deer and antelope playing together without any bickering.

I like it that she tells us what the words mean, words like “discouraging.” She says that “discouraging” means that you don’t like something much, like something makes you feel uncomfortable, something that spoils your spirit.

So now I can say, that “Home on the Range” is my new favorite song. I can also say that recess today, sure was discouraging. But damn, sticking that pocketknife in Tommy Burn’s bully thigh sure felt good. He’s deserved it for a coon’s age.

Maybe there are a few clouds today after all.

Excerpt of No Hill for a Stepper by C. Dennis-Willingham

image credit

via Song

The first day of school, I’m sitting in the back hoping she won’t see me. But she does.

“Cono,” she says, “Sit on up here in front, where I can keep’n eye on you-uh.”

I hate it when she says “you-uh,” like it’s two words instead of one.

Mrs. Berry doesn’t like anything I do. She doesn’t like the way I look, the way I walk, the way I smell, the way I put on my shoes. Well, I don’t like her neither. She stares at me with the corner of her crinkled up eyes, just to find something else she doesn’t like.

“Cono, you’re pressin‘ down too hard with that pencil, you’re gonna break it.” “Cono, I can barely read what you’re writing, it looks invisible.” “Cono, you-uh got something to say or don’t ya?”

She thinks that she’s higher and mightier than God Jesus himself. She walks with her nose so far up in the air that, if she were a turkey, she’d drown. Turkey’s do that. They’re so stupid that if it starts raining, they look up to see what’s dropping on them and sniff!. That’s all it takes. They’ve plumb drown in a drop of rain. You’d think they would have caught on after a while. Like they would have seen their loved ones plop down dead after looking up, that they’d be onto something. No way. They ever look up just to see the pretty stars? Nah. They only look up when it’s raining. Sniff!

The only thing dumber than a turkey is the man that owns them and he’s dumber than a box’a hammers. Just like Mrs. Berry and Principal Pall.

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper by C. Dennis-Willingham

image credit

via Invisible

This Ain’t Us

I didn’t grow up with “Good morning, Cono” smiles or quiet and calm conversations around the supper table. Maybe, we just learned not to speak our mind. Especially since one or two of the minds around the kitchen table might not like our notions.

If somebody were to peek in the window at suppertime, they’d have seen four mouths that moved due to chewing, not from that risky pastime called “talking”. In fact, if we tried to catch each word that came out of our mouths, especially at suppertime, there wouldn’t be enough to fill a soup bowl. And if we were counting on words for our nourishment, well then, we would have starved plumb to death.

I grew up believing that conversation cost money and since those were hard times, Mother and Dad tried to save every penny they could. So if Dad were to tell me, “Son, please leave the pie in front’a Ike’s plate,” it would have cost fifty cents and we could have put that half dollar towards new shoes for Delma.

“Son, the woodpile’s low so I need you to chop the wood today please,” would have cost seventy-five cents and we’d have been chewing on lambsquarters for the rest of our poor lives.

Now on the other hand, when he looked directly at me, pointed to that woodpile and said, “Get busy!” he’d just stockpiled a bundle of money. And if it weren’t for him buying his liquor, we would have had enough money for several good meals and maybe even a new dress for Mother.

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper by C. Dennis-Willingham

image credit

via Fact

Although I’d thought about it many a time, I made it through half of the summer without killing No-Account. So has Aunt Nolie for that matter. Her and that dead-beat husband of hers seem be back to some kind of normal — which for them means the typical bed grunting.

I see No-Account out the window. He’s brought Dad home from another hot springs pool that was supposed to help with his arthritis.

No-Account walks through the door. He’s supporting a man under his arm that looks nothing like my dad. Looks like he weighs no more than a baby bird. Ninety pounds is what they say he is now. Skinny as a rail, not worth a grain of salt. Definitely not strong enough to lift a hand on me — barely strong enough to lift a word.

Excerpt from the novel, No Hill for a Stepper by C. Dennis-Willingham.

painting by Edvard Munch – image credit

via Typical

Delma mashes her little nose up against the window of the car. I stay quiet, thinking about what lays ahead, something I don’t yet know about. I try to picture it, a town with gypsum snow under the ground, a town where Dad is happy, a town where….

“Where we goin’, Cono?” Delma whispers.

“I ain’t so sure Sis, but it’ll be someplace good ‘cause looky here, we’re ridin’ in a four-door automobile!”

She turns away from me then and keeps pressing her little nose up against the window until she finally gives in to sleeping on Mother’s lap. At least we are together, Delma and me. It’s just another place that I plan to watch over her. I want to keep her close by, so nobody can snatch her away again. As long as I can do that, it doesn’t make no difference where we are.

The car keeps humming slowly down the highway. I try to sleep but I can’t. Instead, I think about Mr. Ed Rotan and decide right then and there that “Cono, Texas” has a real good ring to it. Cono, Texas won’t just have snow gypsum under the ground and a railroad on top of it. It’ll have oil underground and derricks on the top, pumping night and day. I call them jacks “grasshoppers” because that’s just what they look like when they’re pumping up and down. They’re grasshoppers trying to hop away, but they’re stuck and have to settle for hopping up and down in the same place.

My town will have at least two good cafés that serve T-bone steaks and tea iced in clean tin jars, free to me since it’s my town.

My mind leaves Cono, Texas and I think again on Ranger, the town where I learned how to brush my teeth, where Ma and Pa have a farm and a house that you’ll always want to go back to, where Polo takes me anywhere I want to go. Ranger is about haircuts that teach you about boxing and about boxing that teaches you to keep standing up. It’s a town where a Tiger can stir the ground and make you a little sister.

Oh yeah. The town of Ranger teaches you that goats freeze, but hands burn.

I go back to the comfort of Cono, Texas, off the poor list and high on the hog. I don’t quite know what to expect, but I sure do like this red brick highway leading to someplace new. I’m thinking that everything’s going to be “copacetic,” like bright colorful times might be ahead, like we’re following a pot of gold at the end of a rainbow.

But I don’t know nothin’ from nothin’.

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper by C. Dennis-Willingham

photo credit

via Restart