Pa always tells me, “Cono, if ye don’t like somebody, it’s jes’t ’cause you hadn’t got to know him well enough’s all.” That sounds like something H. would say.

“Hey, Gene. Ye want to meet a real colored man?” I ask.

“Sure, I do. Who is he?”

So I tell him what I know. I tell him about the man with dark skin and kind eyes. I tell him how he looked at me like I was a real person and not just a stupid little kid.

The next day after school, I take Gene to the barbershop.

“Hi, Mr. H.,” I say.

“Hey there Little Dennis, what you know good?”

“This here’s my friend, Gene.”

“Well, it’s a real pleasure to know ya, Gene,” and he sticks out his hand for Gene to shake. Gene waits a second, stares at H.’s big brown hand, then pumps it up and down like the handle on a water well.

“Well, now that’s a mighty fine handshake ye got there young fella. Ya play any football?”

“No sir, not really. I jes’t throw the ball around a bit’s all.”

“Gene’s real good at throwing the football, H.”

“I can tell that, I shorly can. Besides my wife, Teresa, that’s one thing I love. I love that game ’a football.”

“Why don’t ye play then?” I ask.

“Well, I s’pose that window has closed down on me already, but I been going over to the Yellowhammers’ to watch them practice. They’ve started to let me be their water boy. I sure like it, too.”

“Maybe we kin watch a game with ye sometime,” says Gene.

“Anytime, boys. I’d like that. Uh-huh, shorly would.”

“Ya like shinin’ shoes?” asks Gene.

“Shor I do. I get to talk ta all the folks. Real nice folks here in Rotan.”

The barber’s door jingles as a man walks in. He’s got enough fat on him he could be two people instead of one. After he takes off his cowboy hat and hangs it on a hook, he props up his booted feet on the footrest of the barber’s chair, and says, “Shoe shine, boy.”

“Yes, sir, it’d be my pleasure. Ya better look out now, yer shoes ’re gonna be shinin’ to the next county in jus’ a few minutes.”

The fat man doesn’t say anything. He just opens his newspaper and starts to read while H. starts to Buff his shoes.

Excerpt from No Hill for a Stepper, my father’s story.

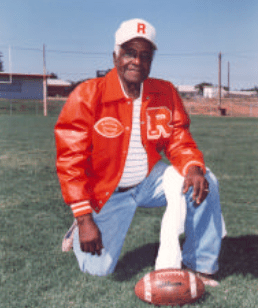

The real H. Govan

Click the H. Govan link to read more about this amazing man.